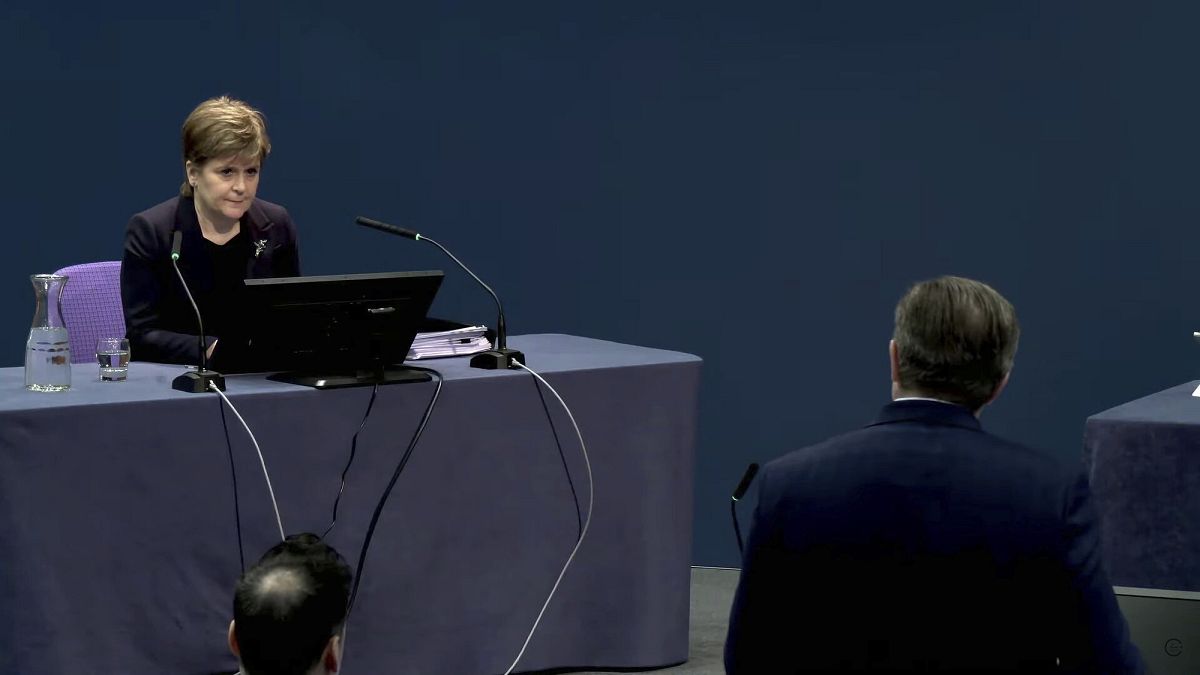

Scotland’s former first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, came close to tears on Wednesday as she told a public inquiry that she struggled with the pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic – and sometimes doubted whether she wanted to be first minister at such a consequential time.

Testifying to the UK’s public inquiry into the pandemic response, Sturgeon said she sometimes felt “overwhelmed by the scale of what we were dealing with,” particularly at the start of the pandemic in the first half of 2020.

“I was the first minister when the pandemic struck,” she said in Edinburgh. “There’s a large part of me wishes that I hadn’t been, but I was, and I wanted to be the best first minister.”

Although Scotland is part of the UK, its government has powers over matters relating to public health.

Much of the rest of Sturgeon’s testimony was tightly focused on the details of particular decisions taken during the pandemic, such as the timing and severity of lockdowns and the decision to close schools.

Sturgeon’s personal handling of the pandemic was well-received by many in Scotland, the UK and beyond. She was widely seen as having a firm grasp of detail and being clear in her public pronouncements, a stark contrast with former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who was ultimately forced to resign partly over his and his team’s flouting of social distancing rules with parties held at 10 Downing Street during lockdown.

However, the view of her pandemic performance has been marred by recent revelations as the inquiry proceeds.

Missing messages

In particular, she and others in her government are facing intense criticism and questioning for deleting many of WhatsApp messages dating from the height of the COVID outbreak, which claimed nearly 20,000 lives in Scotland.

Sturgeon admitted to the inquiry yesterday that she deleted WhatsApp messages, but insisted that she didn’t use informal messaging platforms such as WhatsApp to make decisions.

“During the pandemic I did not make extensive use of informal messaging and certainly did not use it to make decisions,” she said.

Several other witnesses from the Scottish government have been challenged over their messaging practices. Evidence was presented showing exchanges in which civil servants reminded each other to delete group chat messages every day because they would in future be subject to public freedom of information requests.

While Sturgeon conceded that the use WhatsApp had become “too common” within the Scottish government, Sturgeon said she exchanged WhatsApps with no more than a “handful” of people, and wasn’t a member of any groups.

She said she deleted messages in line with official advice that messages could be comprised if a phone was lost or stolen, and that “salient” points were all recorded on the corporate record.

The former first minister said she had “always assumed there would be a public inquiry” and apologised for any lack of clarity at a public briefing in August 2021 where she said her WhatsApps would be handed over – this even though she knew they had already been deleted.

Messages have also been produced in evidence to the inquiry appearing to show she invited a public health expert to communicate with her via her political party email address, rather than her official one.

Last week, Sturgeon’s successor as first minister, Humza Yousaf, offered an “unreserved” apology for the Scottish government’s “frankly poor” handling of requests for WhatsApp messages. He has announced an external review into the government’s use of mobile messaging.

The lawyer representing the Scottish Covid Bereaved group, Aamer Anwar, said Sturgeon had delivered a “polished performance” but that his clients were “deeply unsatisfied” with the explanations around the deletion of WhatsApp messages.

He said the group is considering calling for a criminal investigation into the actions of the former first minister and others.

In the firing line

Sturgeon, 53, became first minister in 2014 after Scotland voted to remain part of the UK in a referendum, and was in office until her surprise resignation in 2023. She was highly regarded even by many opponents of Scottish independence during her tenure, but her political reputation has taken a battering since she stepped down.

Many hardcore elements in the Scottish independence movement remain angry that she was unable to secure another referendum on leaving the UK, which the British Supreme Court has decided the Scottish government does not have the power to legislate for unilaterally.

She is also detested by many allies of Alex Salmond, her predecessor as first minister, who accuse her of engineering his political downfall and prosecution for alleged sex crimes – none of which he was found guilty of committing.

Sturgeon also finds herself embroiled in an ongoing criminal inquiry. Shortly after her resignation last spring, her home was searched as part of a police investigation into the finances of the governing Scottish National Party.

Both she and her husband Peter Murrell, the party’s former chief executive, have since been arrested and released without charge, but insist they have done nothing wrong. The investigation remains ongoing.