One of the main principles of the Schengen Agreement is citizens’ freedom of movement, meaning no controls at the group’s internal borders.

However, there are clauses in the treaty that provide for the temporary reinstatement of border controls, primarily when there is a threat to public order or internal security.

In 2023, at least seven Schengen states resorted to those provisions.

“The Schengen Borders Code allows Member States to reintroduce border controls in the event of a serious threat to their national security, provided the measure is necessary as a last resort and is temporary. Now the Schengen states interpret these conditions very broadly,” says Eugenio Cusumano, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Messina.

According to Cusumano, in this situation, a “domino effect” is created, where the state’s neighbours follow its example.

“The reinstatement of border controls is used as a signal to the public – the government is tough on migration,” Cusumano says, noting that this is a very attractive strategy at a time of rising populist sentiment.

“What we are seeing now is another example of the fragility of the Schengen zone. Germany and now other member states are reinstating border controls. This is happening for several reasons, including political ones. In particular, it has to do with the upcoming elections at local and national levels, putting pressure on central governments,” says Alberto-Horst Neidhardt, head of the migration programme at the Centre for European Policy.

It is also linked to the arrival of large numbers of migrants in southern European countries, he said. Thanks to the lack of borders, refugees move freely across the continent, and some EU countries have seen a sharp rise in asylum applications in recent months. Germany in particular.

Berlin attributes the resumption of border checks with Poland and the Czech Republic to its fight against human traffickers. Slovenia is stepping up surveillance of its border crossings with Croatia, which recently joined the Schengen zone.

“Often it is only a question of spot checks. They only stop a fraction of the people crossing the border. This is not really a full restoration of internal borders. It is a symbolic measure. The Schengen system is perfectly fine. This is one of the greatest achievements of European integration,” political scientist Eugenio Cusumano is convinced.

The Schengen Agreement was signed by five countries – France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg – in June 1985. It took place on the ship Princess Marie-Astrid on the Moselle River, near where the borders of Luxembourg, France and Germany converge.

The treaty was named after the nearest settlement – Schengen.

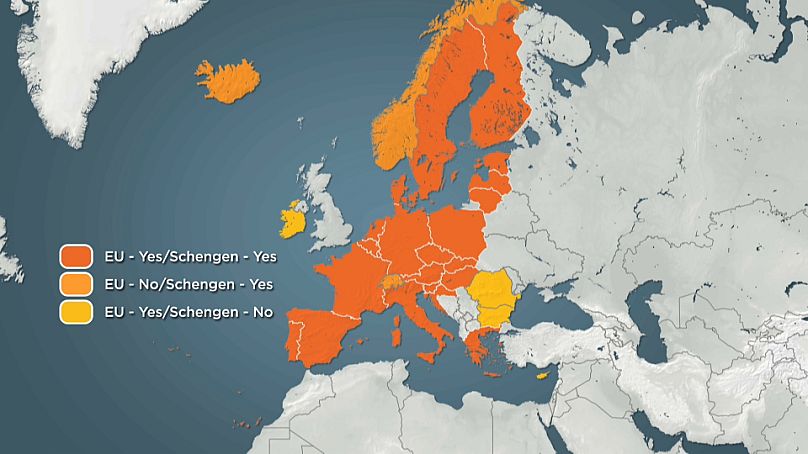

It was later joined by almost all the countries of the expanding European Union, as well as Switzerland, Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein.

Ireland could not join Schengen because of a separate agreement with Great Britain.

Two EU countries – Bulgaria and Romania – have been waiting for more than 15 years to be allowed to join the Schengen group.

Some analysts say this will happen before the end of 2023.

“Million dollar question”: when Sofia and Bucharest will become part of Schengen

The European Parliament has repeatedly urged the governments of the group’s countries to authorise Bulgaria and Romania to join Schengen as soon as possible, noting that they have already fulfilled all the necessary requirements.

In September, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, delivering her State of the Union address, said it should be done “without further delay”.

“This is of course the million-dollar question, and I’m afraid I don’t have a crystal ball to predict when it will happen,” said Alberto-Horst Neidhardt of the Centre for European Policy.

And politics “again plays a big role in this issue,” Neidhardt says.

“All new EU members should be able to enjoy this privilege, a stronger and more sustainable Schengen system.”

“For a long time, it was thought that they were not yet ready and there was a long way to go. But in fact, it looks like they will be part of Schengen by the end of 2023. This could probably be achieved sooner, but at least they are already on that path,” political scientist Eugenio Cusumano told Euronews.

New members need a vote in favour from all countries in the group to be included in Schengen.

The Netherlands and Austria are blocking Bulgaria and Romania from joining, saying they are part of the so-called ‘Balkan Route’ through which a large number of migrants enter the EU.