Their last contact was a late-night phone call.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENTSanooja Saleem’s husband was in tears. He was lost, alone somewhere in the dark, dank border area between Lithuania and Belarus. His phone was running out of battery. He didn’t have food or water.

And then nothing.

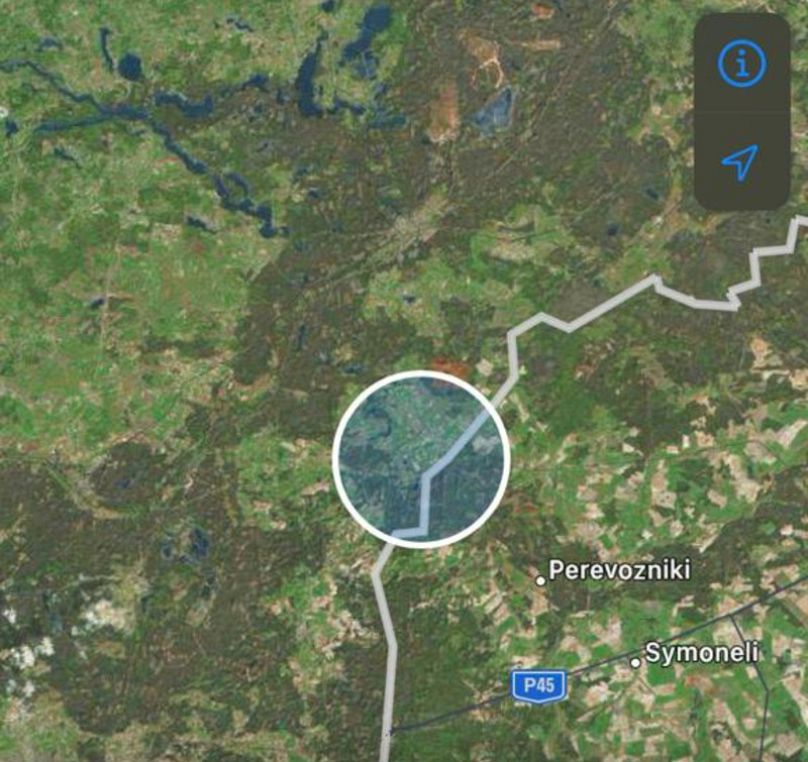

For four and a half months, she tirelessly tried to find out what happened to Samrin, her only clue a fleeting WhatsApp live location shared in the early hours of 17 August 2022.

“Words can’t express how I felt during this time. We had no clue about my husband. Every day my son was asking for his father,” the 32-year-old told Euronews. “We couldn’t sleep.”

As her then four-year-old son Haashim grew increasingly distressed with each passing day, “crying all the time” and refusing to go to school, she contacted the Lithuanian and Belarusian police, who seldom spoke a word of English, and as many institutions, authorities and organisations as possible.

Then her worst fears were confirmed. She received a call the following January that Samrin had passed away, his body recovered from a river months before.

“My husband made a mistake. I accept that. Entering a country without a proper visa is illegal and wrong. I did not support him in this matter.”

“I lost my husband. He was very healthy, young. He’s not a criminal. He wanted to survive, he was suffering. He wanted to keep our family happy. That’s why he came.”

Yet the saga didn’t stop there. As if the news of losing her loved one was not hard enough, the working mum faced the struggle of getting his body back to their home in Sri Lanka.

With Samrin taking on debt to pay for his journey to Europe, Sanooja couldn’t afford to come and identify his body, let alone cover the cost of repatriating his remains.

“I was with my husband side by side through everything. But at that point, I was so helpless. My relatives tried to get me to the funeral but I was not ready. I was not okay with leaving my son.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENTAs a Muslim, “when a person passes away, we have to bury them very soon,” she told Euronews. “We believe dead bodies feel the pain. It was very difficult for me.”

She eventually decided to lay him to rest in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius, but even without her money problems, Sanooja doubted she could get the visa to visit his grave.

It can be difficult for third-country nationals to obtain visas to enter the EU. Visas are often unaffordable, subject to lengthy delays and liable to be refused.

“One day I would like to come and visit him,” she said.

Identifying the dead after shipwrecks

But Sanooja is far from alone.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENTAfter a rickety fishing trawler overflowing with people heading to Italy over the Mediterranean sank in June, relatives are still frantically searching for loved ones among the missing and dead.

An estimated 500-750 people – mostly from Syria, Egypt and Pakistan – are thought to have drowned when the ship capsized, making it one of the deadliest migrant shipwrecks in the Med.

Only 82 bodies have been recovered. The rest, including women and children, sank to one of the deepest parts of the sea estimated at 4,000 m. Here recovery is all but impossible.

For some, the lack of a body to bury means they hold out hope, however improbable, that their wife, brother, friend, sister, husband, lover or son is out there somewhere, still alive. They may never get closure.

Yet, some may be able to close this door.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENTGreek authorities have begun a slow, meticulous, heart-wrenching process to identify the dead.

Complicating their task is a dearth of information about who was on board, as relatives from war-torn and impoverished countries struggle to provide DNA samples, but the Disaster Victim Identification Team have set up a hotline and is still receiving genetic samples.

Their painstaking work continues.

Tragedy is also common in the English Channel, which has seen several devastating shipwrecks in recent years.

Six Afghan men were the latest people to drown when their inflatable dinghy sank in August, according to a UK official.

Many Afghans are running because they served with British armed forces during their military operation in Afghanistan. They are now persecuted, amid reports of vicious reprisals by the Taliban.

When asked by Euronews if it had any formal processes in place to help recover migrant bodies, the UK Home Office did not respond. If their remains end up with the authorities, they also did not say if they would help repatriate them.

What happens when a migrant body is found in Lithuania?

In Lithuania around 30 migrants have been reported missing, while several have died in Poland and Belarus.

One volunteer at Sienos Grupe, a Lithuanian humanitarian organisation, told Euronews how the body of one failed asylum seeker – someone whose application was rejected but still remains in a country – was repatriated from Lithuania.

From the beginning, they said it was chaotic, wishing to stay anonymous.

“We didn’t know who exactly we were talking to when people reached. There was a boyfriend. There was a family back home in Africa. It was very messy,” they explained.

Friends of the deceased eventually stepped in as translators and organisers, while other humanitarian organisations got involved. Their body was eventually repatriated, but only after a lengthy process that cost massive amounts of money and effort.

Though support was out there, the aid worker worried for families who faced language barriers lacked the resources or did know which institutions to contact to find out about deceased loved ones.

“The situation is weird, to say the least,” they said, claiming it was unclear how authorities helped repatriate migrant bodies or if a formal system existed.

Citing the case of a dead man from India, who was found on the Lithuania-Belarus border in April, they explained: “We have no idea how he is represented, how his case is being handled, we don’t know if the family receives any kind of aid to repatriate his body.”

“Maybe they are doing stuff behind our backs. But I feel like a lot of the time when the state is doing something good they want people to know.”

Sanooja praised the Lithuanian authorities, Sienos Grupe and the Lithuanian Red Cross who “gave their full support” and were “very kind”, as she tried to lay her husband to rest.

Several dead migrants – including children – have been buried in Lithuania at the expense of the state because relatives could neither come nor collect their bodies, a Lithuanian Red Cross Restoring Family Links coordinator said in a statement sent to Euronews.

However, the Lithuanian Interior Ministry did not answer Euronews’ request for information about whether it helps send migrants’s bodies home or covers the cost.

They also did not disclose how people can check if a body has been recovered or if officials attempt to find a person’s relatives if their remains are unclaimed.

“If state border guards discover human remains at the border, regardless of gender, age or other circumstances, they shall immediately secure the scene and call the police,” Lithuania’s border guard told Euronews.

For the Sienos Grupe volunteer, this ambiguity about what happens to migrants in death reflects a wider issue about how they are viewed in life.

“There’s a lack of care and dehumanisation of these people,” they told Euronews, suggesting caring about their bodies could fix this.

“Death is universal for all of us as people, it is something we all experience, we all bury our dead. It’s holy… If we care about their bodies, then we should care about migrants and should start preventing their deaths at the border.”

“If we keep this situation low key and act like it is just a body and not a human with a world inside of themselves, a past, future, maybe children, someone who was loved, then it’s easy to brush everything under the rug.”