Fears Britain’s largest water company is teetering on the brink of collapse, repeated strikes on ailing railways, households hammered by sky-high electricity and gas bills: the UK’s vital sectors are in crisis, decades after controversial privatisations.

Under the Conservative governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major, state-owned companies were broken up and sold off to the private sector in the 1980s and 1990s.

The move brought new investment but also huge executive bonuses, shareholder dividends and massive debts.

Debt-ridden Thames Water, the company managing the water supply of the London area, announced on Monday it had raised €880 million from its shareholders.

But the company, whose financial stability worries even the British government, has a debt of nearly €16 billion.

The Conservative government said in June it was ready for any scenario, amid concerns the largest water company in the UK may go under.

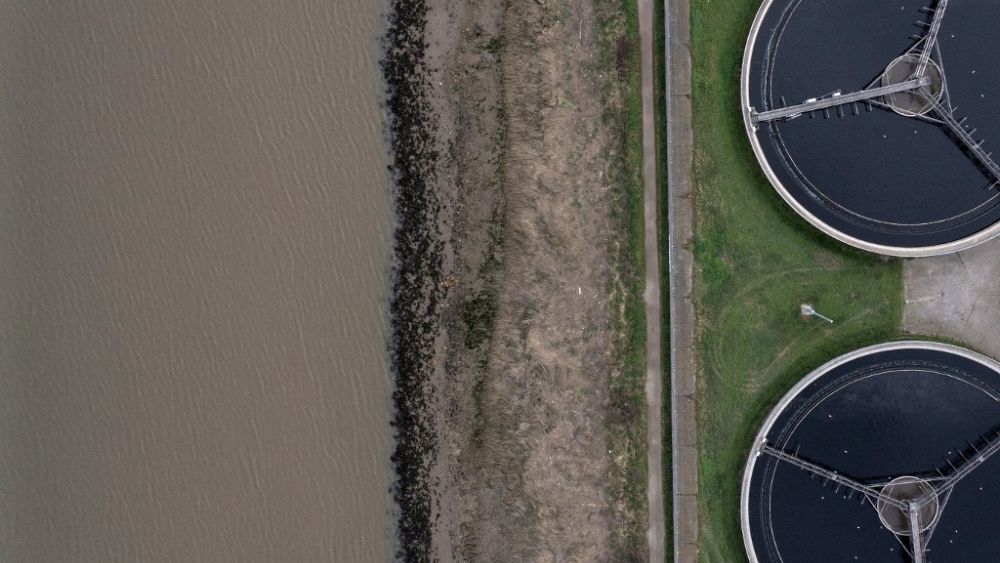

Serving 15 million customers in and around the British capital, Thames Water – along with other water suppliers – has also repeatedly hit the headlines in recent months for dumping raw sewage in the country’s waterways.

According to the press, officials are working on an emergency plan that could allow – if necessary – the state to regain control of Thames Water.

Such renationalisation would carry a high cost, yet the idea is popular with the electorate. A 2022 YouGov Poll found that most Britons believe that trains, water and energy should sit within the public sector.

Delays and cancellations

The right-wing Conservatives have long favoured privatisation.

However, the opposition Labour Party have jettisoned plans to renationalise water, energy and the Royal Mail postal service, though they still plan to bring the railways back under state control.

“It’s easier for the rail sector because it’s already largely nationalised,” Hugh Willmott, professor at the Bayes Business School in London, told AFP.

Britain’s railways have in fact not been fully privatised, with private operators given state funds to run and upgrade their services.

Some claim that the large bonuses these companies pay to their shareholders amounts to a transfer of taxpayer’s money to private individuals.

Authorities have also implemented temporary renationalisations of certain poorly managed operators. In May, they took control of the TransPennine Express, operating in northern England and parts of Scotland, amid multiplying delays and cancellations.

The impact of privatisation on public companies has been denounced by several unions, while rail workers, medics and postal workers have walked out in recent months over pay and conditions.

One vital sector remains under state control: the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), which has just celebrated its 75th anniversary, but is facing a deep crisis too.

Speaking to Euronews in January, experts said staff shortages – compounded by Brexit – and chronic underfunding have helped bring the service to its knees.

“When it was privatised in 1989… the water sector was hailed as a success of the privatisation programme under Thatcher,” independent analyst Howard Wheeldon told AFP.

“The sad reality is that, in a world increasingly dominated by individual greed, … the water sector has become the biggest fraud story in the UK,” he continues.

“In 34 years of privatisation, water bills have skyrocketed.”

Meanwhile, water companies racked up more than €70 billion in debt over the period.

Water companies are also under fire for dumping large quantities of sewage into rivers and the sea, amid a lack of investment in the country’s water system that dates back to the 19th-century Victorian era.

While water companies are privatised in England, the situation differs in other parts of the UK, where they are not-for-profit.

Some have argued that privatisation helps reduces money for investment by channelling profits to shareholders.

“Would nationalisation, itself a long and expensive process, be an improvement over better regulation of the private sector?” asks Professor Len Shackleton of the pro-free trade think tank The Institute of Economic Affairs.

“Certainly, the costs would be reduced if no dividends were paid. But public borrowing always has a cost. (…) Do not believe that nationalisation is the panacea”, he warned.